Washington Artillery Arsenals

Home Sweet Home

The Bricks and Mortar of the Washington

Artillery

Historic Jackson

Barracks in the outskirts of New Orleans has always been the training ground for

the Washington Artillery. Built in the 1830s and named after the famed commander

of the Battle of New Orleans, Andrew Jackson, the grounds served both federal

and state troops. However over the centuries, the battalion also

maintained an arsenal within the city proper.

The Cabildo

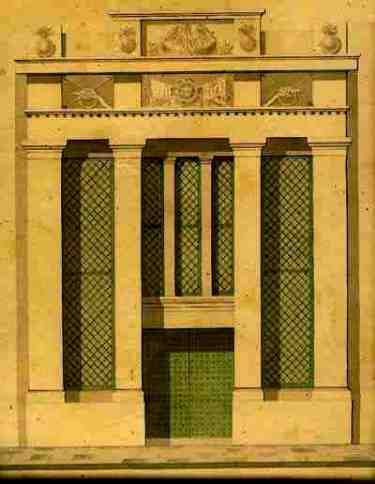

Architect Joseph A. Darkin's drawing of the

arsenal at the Cabildo.

(courtesy Louisiana State Museum)

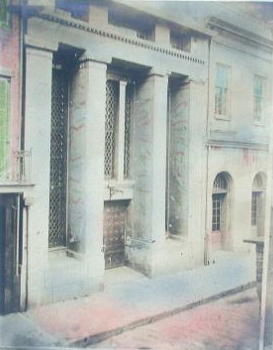

First Arsenal of the Washington Artillery

near the Cabildo

while serving under the Louisiana Legion

(photos circa 1930s)

In February,

1821, the governor of Louisiana was authorized by the legislature to buy four

4-pounder cannon with carriages, for the use by New Orleans militia uniformed

organizations. Each of these units were required by law to drill at least once

per month. It was this same year that a new militia unit called the Louisiana

Legion was organized. “Legion”* simply meant a military unit composed of four

companies, each organized with infantry, cavalry, and artillery. The two artillery companies of the older Battalion

of New Orleans Volunteers, one of which was known as the Washington Artillery,

merged to become the fourth company of this new legion. This newly consolidated

artillery company, the Washington Artillery, was housed in the rear of the Cabildo. The lattice ironwork of the balcony still displays the initials “L. L.”

(Louisiana Legion) along with the flaming bomb, a symbol of artillery. This was

the earliest known armory of the Washington Artillery. In keeping with its

status amongst the community, the Washington Artillery was given the honor of

firing a cannon salute and forming the honor guard when the Marquis de

Lafayette, fighting companion of George Washington in the American Revolution,

visited New Orleans in 1825.

(*Actually, the term “legion” dates

back to Roman times when it designated a military unit of 1000 men, composed of

landowners only, and was derived from the Latin word meaning “conscription”. As

with its American counterpart, it was composed of “citizen soldiers” concerned

with protecting their homeland and property.)

Girod Street

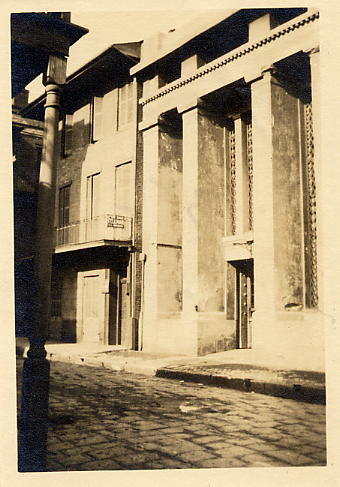

Girod Street Arsenal

(center of photo to the left of fire

station.)

Built in 1858. Burned, confiscated, and sold

in 1867.

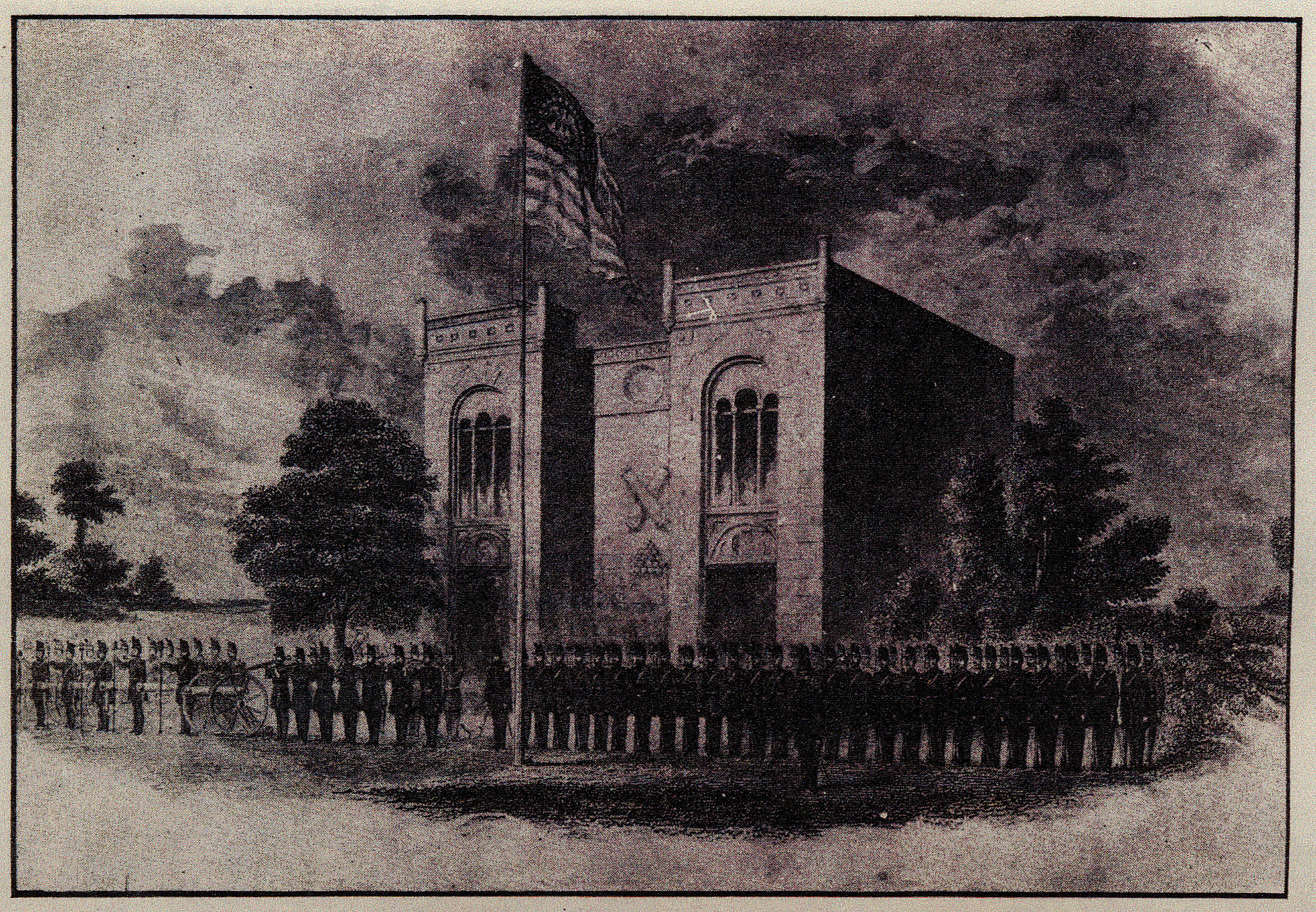

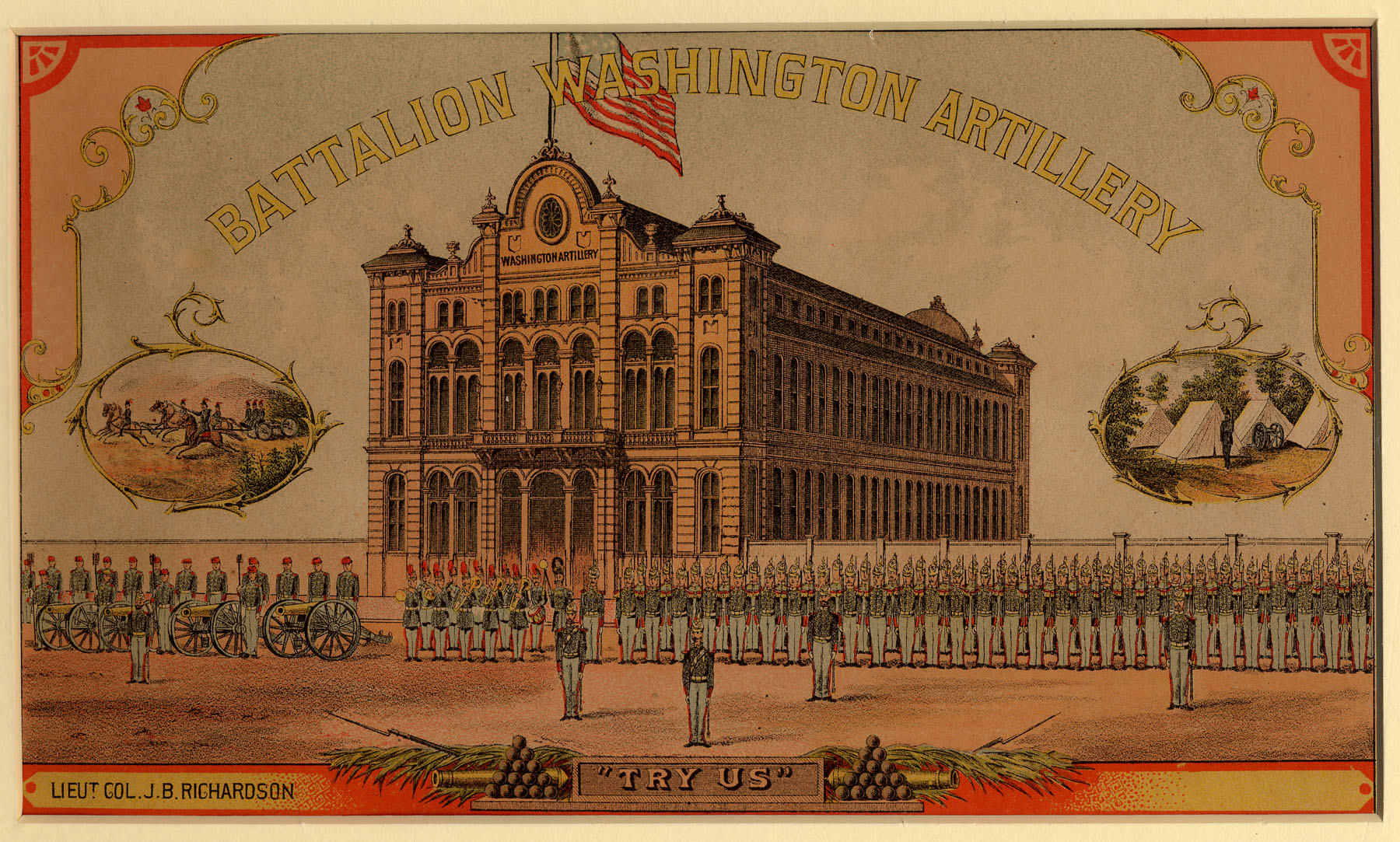

Lithograph of Battalion Washington Artillery

in front of their Girod St. Arsenal-circa

1860

In the

1840s the Washington Battalion was stationed in a former blacksmith shop on Girod Street, between St. Charles and Carondelet Streets, in New Orleans. It was

gradually adapted for military purposes and named the Washington Battalion

Arsenal. The Washington Artillery (then known as the Native American Artillery)

moved from its arsenal in the Cabildo to the Girod Street location.

After the Mexican War, the

Native American Artillery was sent home with the gratitude of the federal

government. In appreciation of their service, the State of Louisiana

appropriated $30 a month to help maintain their armory and,

in recognition of the organization’s services, the City of New

Orleans donated the Girod Street building previously used by the group as an

armory “as long as the Washington Artillery remains in possession of the city’s

cannon.” William A. Freret, New Orleans architect and member of the artillery

unit, designed plans for an upgrade of the old converted building. During its

renovation, the arsenal was a scene for many a gala. The New Orleans Delta

described a July 6, 1855 event,

“After the review in Lafayette Square, the Continental Guards presented the

Washington Artillery with a beautiful American flag, in presence of the entire

brigade, which had formed in a square. Captain Labuzan, in presenting the flag,

made a very handsome address, which was eloquently responded to by Captain

Hunting of the Washington Artillery. The ceremony of presentation finished, the

Artillery escorted the Continentals to the armory of the former company in Girod

Street, where, stacking arms, they all marched together to the residence of

General [E. L.] Tracy [former commander of the Washington Artillery now in

charge of the state militia].

Here the veteran General had prepared an excellent collation, which was

partaken of sans ceremonie, with a hearty good will by what might not

inappropriately be styled the hungry brigade—for the early hour at which the

military were ordered out, prevented most of them from breakfasting. Previous

to the collation Capt. Labuzan, on behalf of the Continentals, presented Gen.

Tracy with a service of plate as a token of their esteem. The two companies

then returned to the Washington Artillery Armory, where several huge bowls of champagne punch had been

prepared, together with "something to eat." Here, of course, all restraint was

thrown off, a pleasant half hour was passed in soldierly social intercourse,

about which we might write a column, but have neither time nor space. The

Artillery then escorted the Guards back to their own armory on Camp street, and

here they separated; the best good feeling prevailing, which it is hoped will

continue to prevail so long as these two companies maintain their present high

position and reputation.”

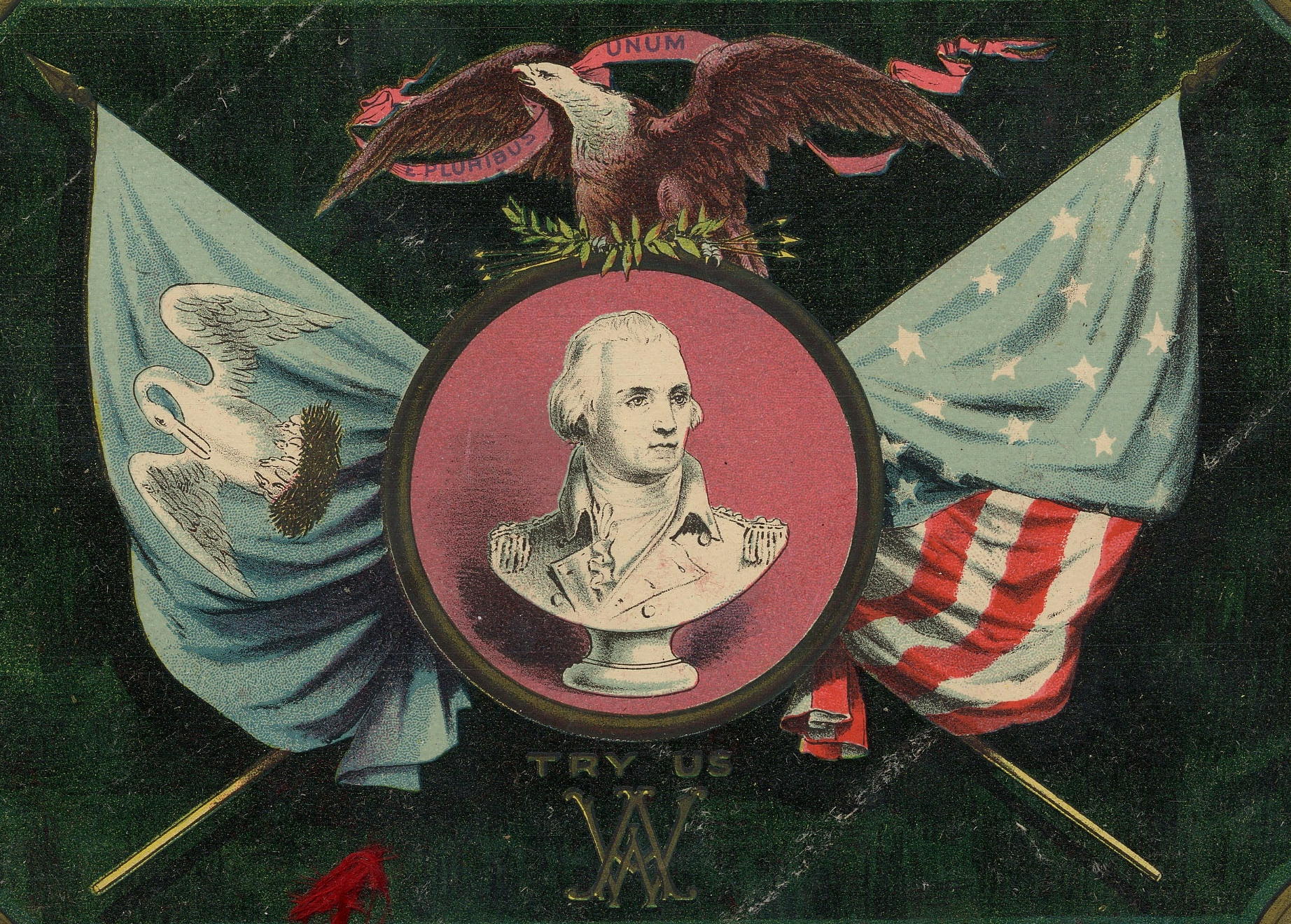

By 1858,

under the direction of Commander James Walton, the building was finally taking

shape as a first class facility. Its exterior military façade was

finished, complete with two medallions of George Washington’s profile,

four cannon incorporated in its pediment and crossed cannon above a stack of round cannon balls.

Its architect was the brilliant William A. Freret, son of the mayor, and member

of the unit. Here the unit grew to a full company, splendidly uniformed and

equipped at member expense. It drilled in infantry as well as artillery tactics.

The arsenal housed both rifles and cannon, but continued to act as a site for

many social events.

In

1861 work was still progressing on the facility. But more important matters were

at hand.

On May 26, 1861 the battalion, dressed in new militia uniforms of blue

and with a fine band (Gessner’s Brass Band), marched into Lafayette Square, where

it was mustered into Confederate service for the “duration of the war.” The

Washington Artillery now consisted of four companies. Two

companies were equipped as artillery and two as infantry. From there its members

marched to Christ Episcopal Church on Canal Street where its rector, Dr. Leacock,

proclaimed to them, “Our hearts will follow you, and our prayers will ascend for

your safety and return.” The

following day the battalion left their arsenal on Girod Street, the roof not yet

put on, the floors torn up. It then paraded past City Hall where the Reverend

Benjamin M. Palmer of the nearby First Presbyterian Church wished the unit “God

speed.”

After the fall of New Orleans in 1862 and while the Washington

Artillery was in the service of the Confederate government, Union forces seized the

arsenal. Union General Benjamin Butler ordered federal soldiers to

burn the building. The battalion's old records and early history, impossible to

replace, went up in flames with the structure. All that survived was the front

wall and its façade. After the war, the facade was moved to a park across from

Jackson Square which was named Washington Artillery Park, in honor of the city's

veteran artillery unit.

The facade of the Girod Street Arsenal as it

looked in the 1970s

at the Washington Artillery Park across from

Jackson Square.

The Washington Artillery Monument has one of

the unit's original cannons.

Temporary Quarters

Washington Artillery

veterans returned to the city after the Civil War to find their arsenal in

shambles. Benjamin Butler had confiscated and destroyed the Girod

Street structure by fire during his occupation in 1862. The federal military

government in charge of the city during Reconstruction continued the insult by

selling the remnants of the burned out armory “of the rebels” in 1866 and

keeping the proceeds. Since Confederate veterans were not allowed to bear arms

or form any military organization, Washington Artillery members were forced to

meet wherever possible as the Washington Artillery Benevolent Association.

Finally on May 25, 1870, the battalion was allowed to reorganize by order of the

general of the state militia, ex-Confederate General James Longstreet. A new

arsenal was needed. The Washington

Artillery occupied temporary armories on Perdido, then Common Streets (opposite

the Medical College), until it raised sufficient funds through subscription of

its own members to purchase a new arsenal.

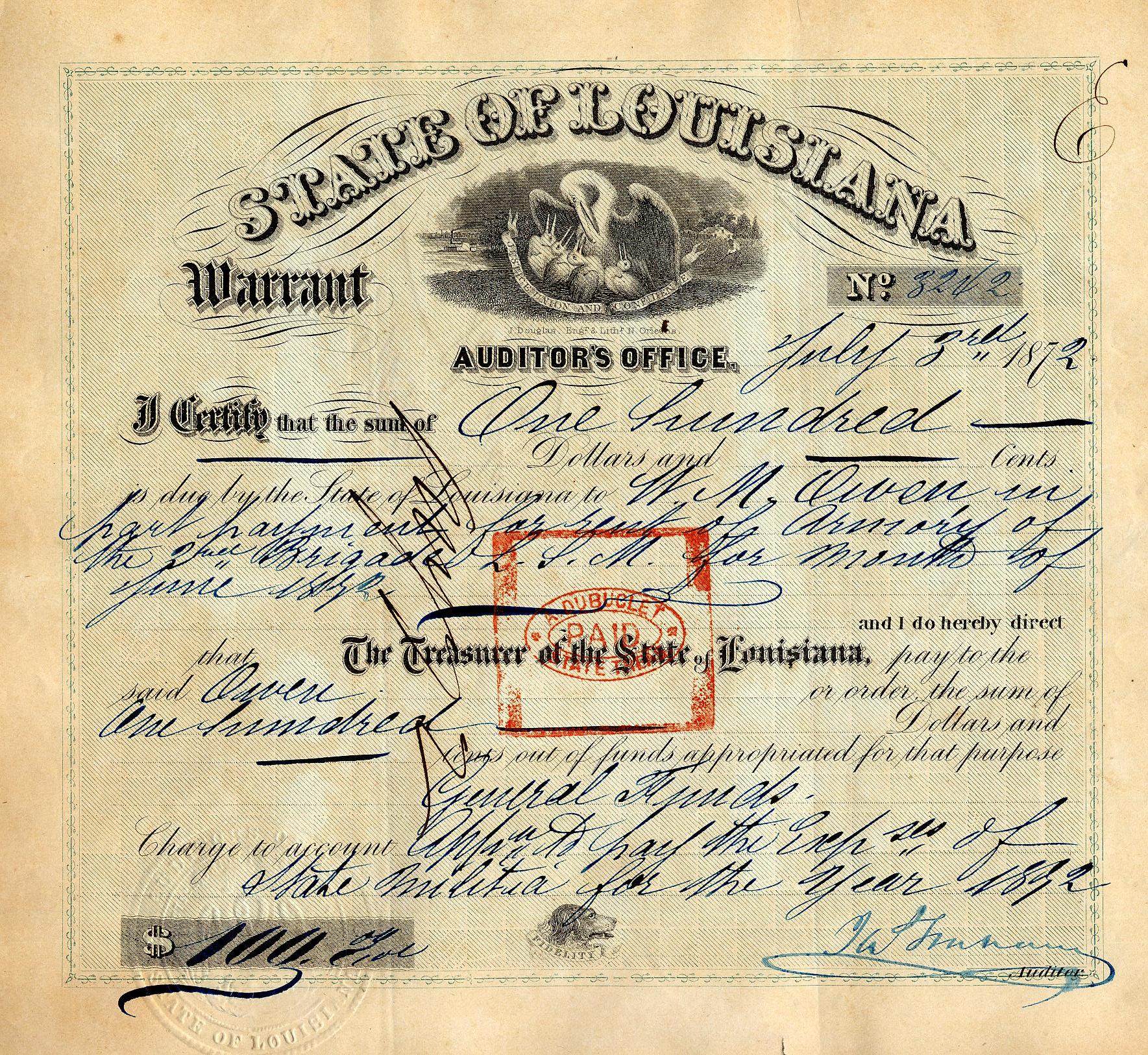

Partial payment

from the State of Louisiana to William Miller Owen dated July 3, 1872 for rent

of the armory for the Second Brigade Louisiana Militia.

St. Charles Street

St. Charles Street Arsenal

John B. Richardson,

the Washington Artillery's then commander, found a splendid candidate for its

new arsenal in 1878 in the massive building on St. Charles Street, previously

built in 1865 and used as an exposition hall for the 1872 Grand Industrial

Exposition held in New Orleans. This three storied structure, which faced St.

Charles Street and ran all the way through to Carondelet Street (90 x 360 feet), was

called Exposition Hall. It was bought in 1878 by the Washington Artillery,

renamed Washington Artillery Hall, and used as their arsenal. Besides owning the

property, the battalion managed to totally reequip itself with its own cannon,

rifles, sabers, uniforms and ammunition. A shooting range was even constructed

within the facility, a luxury for the time.

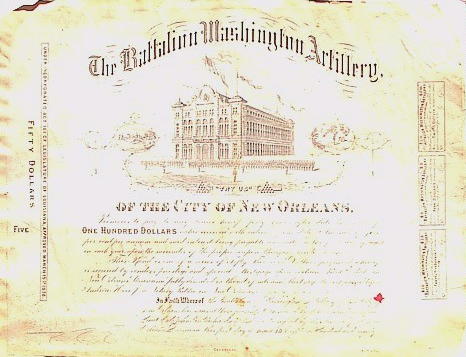

Stock issued to raise the funds needed to

buy the Louisiana Exposition Hall and convert it to the Washington Artillery

Armory, circa 1880s.

Color lithograph of the battalion in front of the

St. Charles St. Arsenal

This litho was

used in the center of the above noted stock-circa 1880s

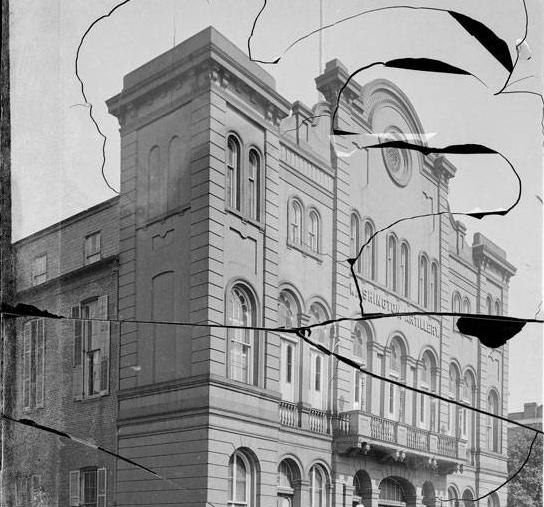

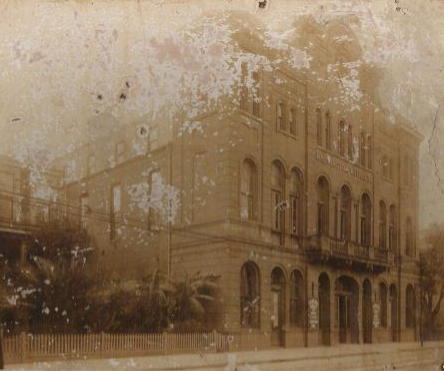

St. Charles Street Arsenal

Battalion Washington Artillery parades in front of

its St. Charles Street arsenal-circa 1890s

Stereoview albumen by

S.T. Blessing of

the St. Charles St. Arsenal

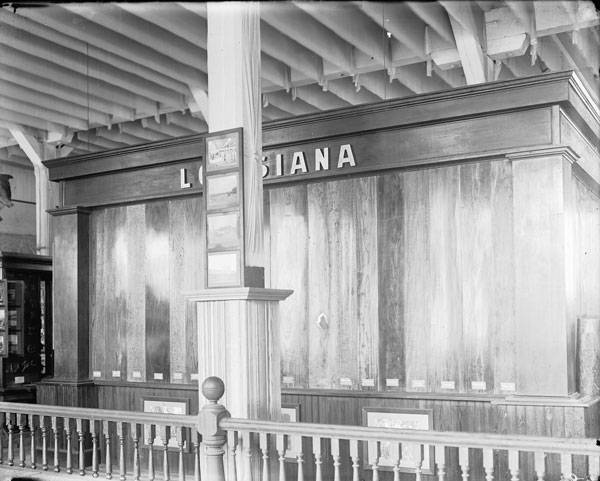

Interior of the arsenal

as seen during the Louisiana Exposition in 1903.

However, the hall’s

huge second floor ballroom was also used for many social balls, including

Carnival. (The grand hall had played host to the King of the Carnival’s first

Reception Ball in 1873.) Although the facility was not adapted for tableaux and

had a limited seating area, Washington Artillery Hall became renowned as the

Carnival Palace of Rex and his royal consort from 1879 until 1906. In fact,

several prominent ex-Confederate veterans and Washington Artillery families

reigned as kings and queens in the great hall. Philanthropists Charles T.

Howard (1877) and Frank T. Howard (1895), the latter the founder of the

Confederate Memorial Hall museum, were kings; Cora Slocomb (1881) and Bessie

Behan (1891), a daughter and a wife of WA veterans respectively, were queens.

Mardi Gras balls were

held within the arsenal.

In 1882 the Washington

Artillery started holding its annual reunions there. During its 1883 reunion, the

battalion was presented with one of the three original prototype presentation battle flags of

the Confederacy. Made by Jennie Carey for P.G.T. Beauregard, the old “Creole”

himself, this flag was presented by Alfred Roman in lieu of a sick Beauregard.

The flag was held in great esteem, kept in a case and removed on only two

occasions, to cloak the coffins of Beauregard and Confederate President

Jefferson Davis. Washington Artillery Hall also served as the home for the celebrated,

monumental 10 x 12 foot oil painting by Everett B. D. Julio, representing the

last meeting of Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson at the Battle of Chancellorsville

[now owned by and exhibited at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond,

Virginia.].

(courtesy Museum of the Confederacy)

The magnificent hall

was the scene for many more important events in the social, political, and

military annals of New Orleans, including presentations associated with the

Annual Meetings and Reunions of the United Confederate Veterans Conventions held

in New Orleans in 1892 and 1903. The structure finally fell out of favor to more

modern facilities in the 20th century. The Washington Artillery moved

its arsenal to its old practice grounds at Jackson Barracks in 1922, but

continued to use the St. Charles Street property at times.

When the military unit

returned from fighting in World War II as the 141st Field Artillery,

it decided to permanently reside at the larger Jackson Barracks location. For a brief time (1968) the unit was stationed at the site of old Camp

Nichols (the ex-Confederate veteran’s home) on Bayou St. John. Prior to the

unit’s departure from the St. Charles arsenal, many of its artifacts, mainly

post-Civil War, were transferred to the collection of the Louisiana State

Museum, where they are still currently housed. Most of the unit's Civil War era

artifacts were donated and housed at Confederate Memorial Hall, where they also

remain today. The St. Charles Street arsenal

was sold and became a car dealership but by the 1950s fell into disrepair and

was finally demolished in 1952 to make way for an office building.

The St. Charles Street Arsenal

in the 1950s at the time of its demolition.

(1903 and 1950s B&W photos courtesy

LOUISiana Digital Library)

HOME