The most feared enemy of the Confederate soldier was not dressed in blue. It lurked in the shadows of camp life and the gun flashes of the battlefield. Diseases and gunshot wounds took the lives of more Confederate soldiers than all Confederate battlefield fatalities combined. And unfortunately, the medical technology available to Confederate physicians and surgeons was as antiquated as their philosophies of treatment. But most Confederate surgeons, despite their limitations, did have good education for the time. The University of Louisiana’s medical school located in New Orleans, called the Medical School of Louisiana, was founded in 1834 and had a steady growth in enrollment from 1850 (35) to 1861 (133). 1861 one Confederate medical student noted the institution to be “a superior school-the best in the Confederacy-I doubt not.” Due to the massive exodus of its students to join various military units and the fall of the city of New Orleans into Union hands in 1862, the medical school was forced to close for the duration of the Civil War.

Charity Hospital of New Orleans also served as a teaching ground for future military surgeons. Founded from the proceeds bequeathed from the will of a French merchant seaman in 1736, the facility had progressively expanded to become one of the largest in the world at that time, accommodating a staggering 1,000 patients. During the seven years that preceded the Civil War, between 12 to 18 thousand patients were admitted each year. Although this hospital provided a means of excellent education for its physicians, it could not begin to prepare these doctors for the management of horrors they would have to witness in the bloody years to come.

Initially however, the surgeons of the Washington Artillery faced medical problems that occurred when such a large group of people was thrown into large and unsanitary conditions-that is, a variety of diseases. Commutable diseases such as measles, typhoid fever, malaria, dysentery and those sexually transmitted ran rampantly through their camps. John Harris wrote to his wife in 1861, “I went to one Hospittle [sic] yesterday to see for my own self. Their [sic] were 27 men in there sick. Their disease was from measels [sic] down to the rottonest [sic] disease that man can take, from (women).”

When Confederates finally saw action, battle casualties were added to the Southern medical staff’s already taxed facilities. Bullets caused more than 90% of all wounds. Those wounded soldiers who were fortunate enough to make it off of the battlefield found them in a field hospital. Makeshift field hospitals were usually set up within private homes, farm buildings or large field tents. The wounded were triaged by assistant surgeons into one of two categories: wounded and mortally wounded. Wounds of the abdomen or chest were considered “mortal,” or fatal, and could not be treated. Those poor souls were comforted and gathered to die in peace. Those wounds involving only the limbs were considered treatable. Treatment of shattered limbs consisted of amputation under anesthesia. Anesthetics were limited to chloroform, ether, whiskey and sometimes the relatively new drug morphine. The favorite and most available to Southern surgeons was chloroform. “In all our operations,” declared the Louisiana Hospital’s Felix Formento, “we invariably used chloroform.”

If a wounded soldier made it past his surgery, he was confronted with the unseen threat of infection. If a wounded soldier did not get his wounded limb amputated, he might develop infectious gangrene; however, if he HAD his wounded limb amputated he might also develop gangrene- not great odds. This was because antibiotics such as penicillin had not been yet discovered, and the surgeon’s tools used for amputation were unsterile.

If the amputated soldier was lucky enough to survive, he found himself evacuated to a Southern general hospital where he was placed under the following orders: compassion, comfort, and convalescence. Here he would either be discharged from service or returned to the army, usually the invalid corps.

Convalescing soldiers had time to reflect and hope. A sick private at Camp Moore’s infirmary wrote home about his prognosis, “I put my trust in God … that I may be spared to get up and return home again in peace and plesure [sic] once more.”

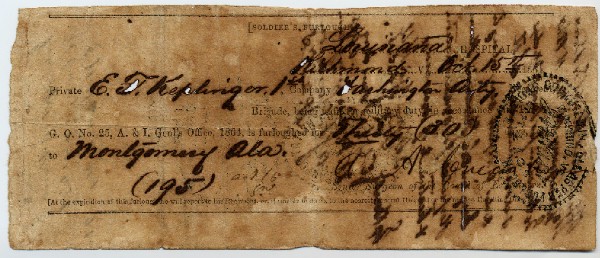

Medical furlough for a Washington Artillerist E. F. Keplinger, First Company

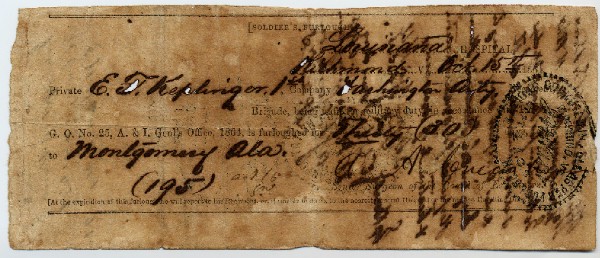

Dr. E. S. Drew, surgeon of the Washington Artillery, was present during all of the marches and battles of companies 1-4.

He was called “Drugs” by the boys of the battalion and was noted as an “experienced sawbones” by Lt. Col. Owen.

John Eaton Pugh, assistant surgeon of the 5th Company, joined the unit on May 4, 1862 and was present during the Kentucky campaign and Murfreesboro.

However, he was assigned to the 1st & 3rd Florida later that year on December 31, 1862 and was eventually stationed at Hurricane Springs Hospital.

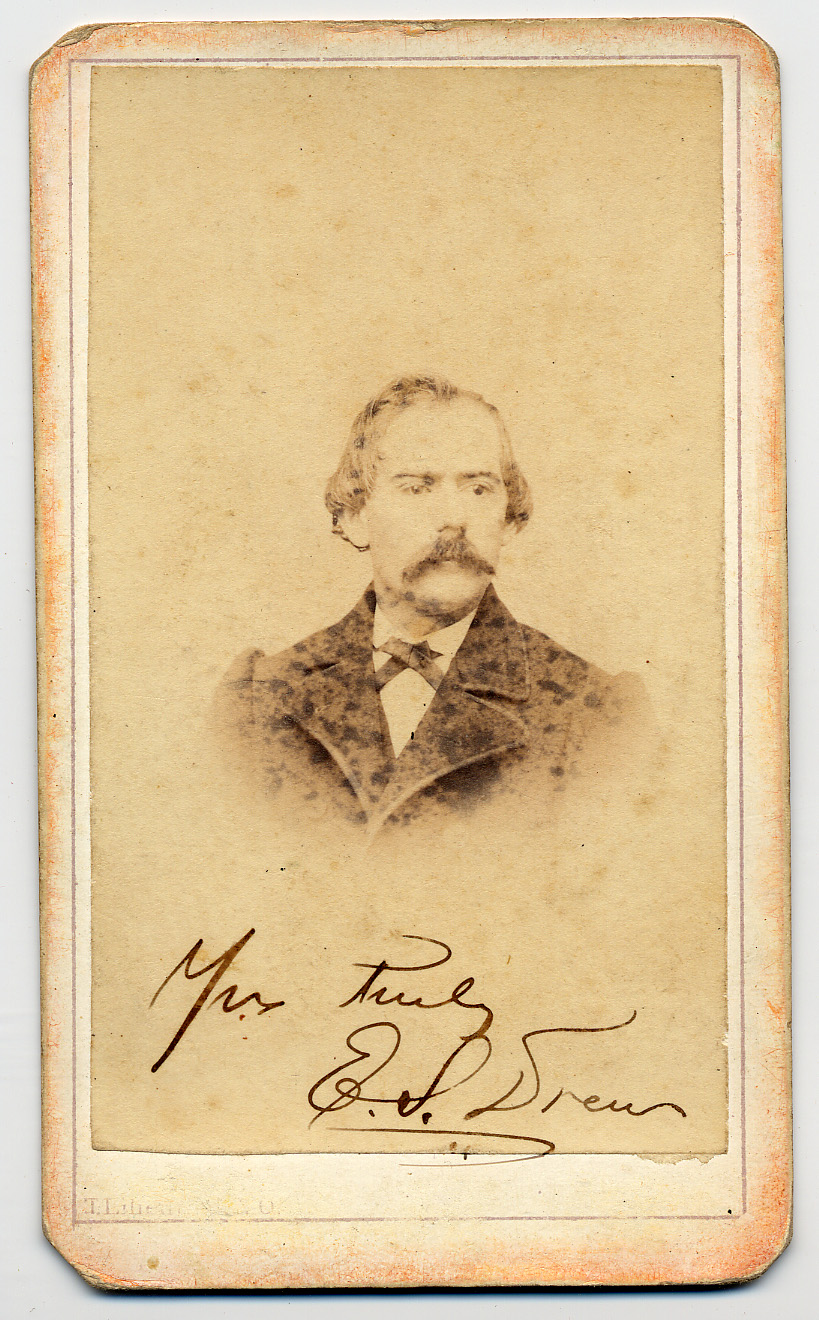

William P. Brewer was a 20 year-old student when he enlisted May 26, 1863 as a private in Washington Artillery’s 3rd Company, and was soon detailed as a hospital steward on June 10th of that same year. He was promoted to assistant surgeon and maintained this rank until the end of the war. He is pictured here in his postwar Washington Artillery uniform (circa 1884).

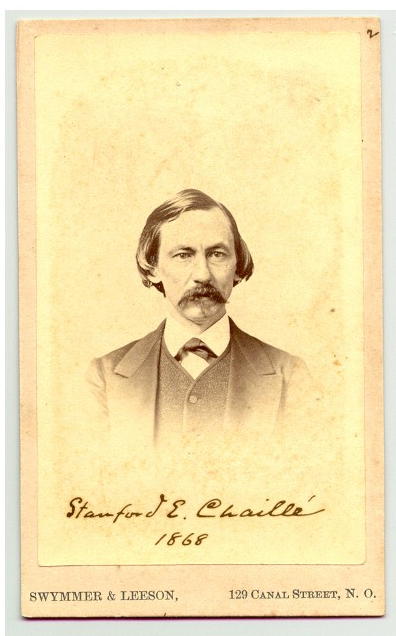

S. E. Chaille

This Confederate Louisianian commanded the Ocmulgee Hospital in Macon, Georgia.

He would later become President of Tulane University.

He signed the death certificate of President Jefferson Davis.

HOME